Blog

Massachusetts has stretched its energy code since 2009, making it the first state to implement a stricter, above-code option. This occurred as part of the Green Communities Act, where municipalities are provided financial and technical support if they meet specific energy reduction goals and criteria.

In 2023, Massachusetts adopted the 2021 IECC as its base energy code. The residential low-rise Stretch Code went into effect January 1, 2023, and the commercial Stretch Code went into effect July 1, 2023, with a transitional period until 2024.

While the entire state adopted the base code, Massachusetts lets municipalities adopt the Stretch Code or the Opt-in Specialized Code, allowing flexibility of energy efficiency standards locally while still aligning with the state’s greenhouse gas emission reduction and net-zero goals by 2050.

Of the 351 town and cities in Massachusetts, roughly 301 have adopted the Stretch Code and 41 have adopted the Opt-in Specialized Code. (Click here to download the Building Energy Code Adoption by Municipality map from Mass.gov.)

Learn more about SWA’s Massachusetts Stretch Code consulting >>

Low-rise multifamily, attached (townhouse style), and single-family homes fall under the residential section of the code. Compliance is based on the HERS Index Target with additional ventilation, electrical-vehicle-ready, and solar-ready requirements. Passive House is an optional compliance path for residential buildings under the stretch code.

The specialized code is based on the 2021 IECC Appendix RC, Zero Energy Residential Buildings, which requires zero-energy or all-electric buildings, with limited compliance options for electric-ready, mixed-fuel buildings. All compliance options require buildings to be EV-ready as well as either on-site renewables or solar-ready buildings.

While building size may dictate the appropriate path for commercial projects (including multifamily over three stories), there are five compliance paths:

In addition to the Stretch Code, the Opt-in Specialized Code requires new buildings with any fossil fuel uses or biomass heating to include the following:

The following table illustrates the required HERS score based on project type, fuel usage, and renewable energy.

TABLE R406.5 MAXIMUM ENERGY RATING INDEX

| Clean Energy Application | Maximum HERS Index scorea,b | ||||

| New Construction permits after July 1, 2024 | New Construction with R406.5.2 embodied carbon credit | Accessory Dwelling Units | Major alterations, additions, or Change of usec | ||

| Mixed-Fuel Building | 42 | 45 | 52 | ||

| Solar Electric Generation | 42 | 45 | 55 | ||

| All-Electric Building | 45 | 48 | 55 | ||

| Solar Electric & All-Electric Building | 45 | 48 | 58 | ||

a Maximum HERS rating prior to onsite renewable electric generation in accordance with Section R405.6

b The building shall meet the mandatory requirements of Section R406.2, and the building thermal envelope shall be greater than or equal to the levels of efficiency and SHGC in Table R402.1.2 or Table R402.1.4 of the 2015 International Energy Conservation Code.

c Alterations, Additions or change of use covered by Section R502.1.1 or R503.1.5 are subject to this maximum HERS Rating, except for Historic buildings which may opt to follow the prescriptive compliance pathway in R401.2.1.

Table notes:

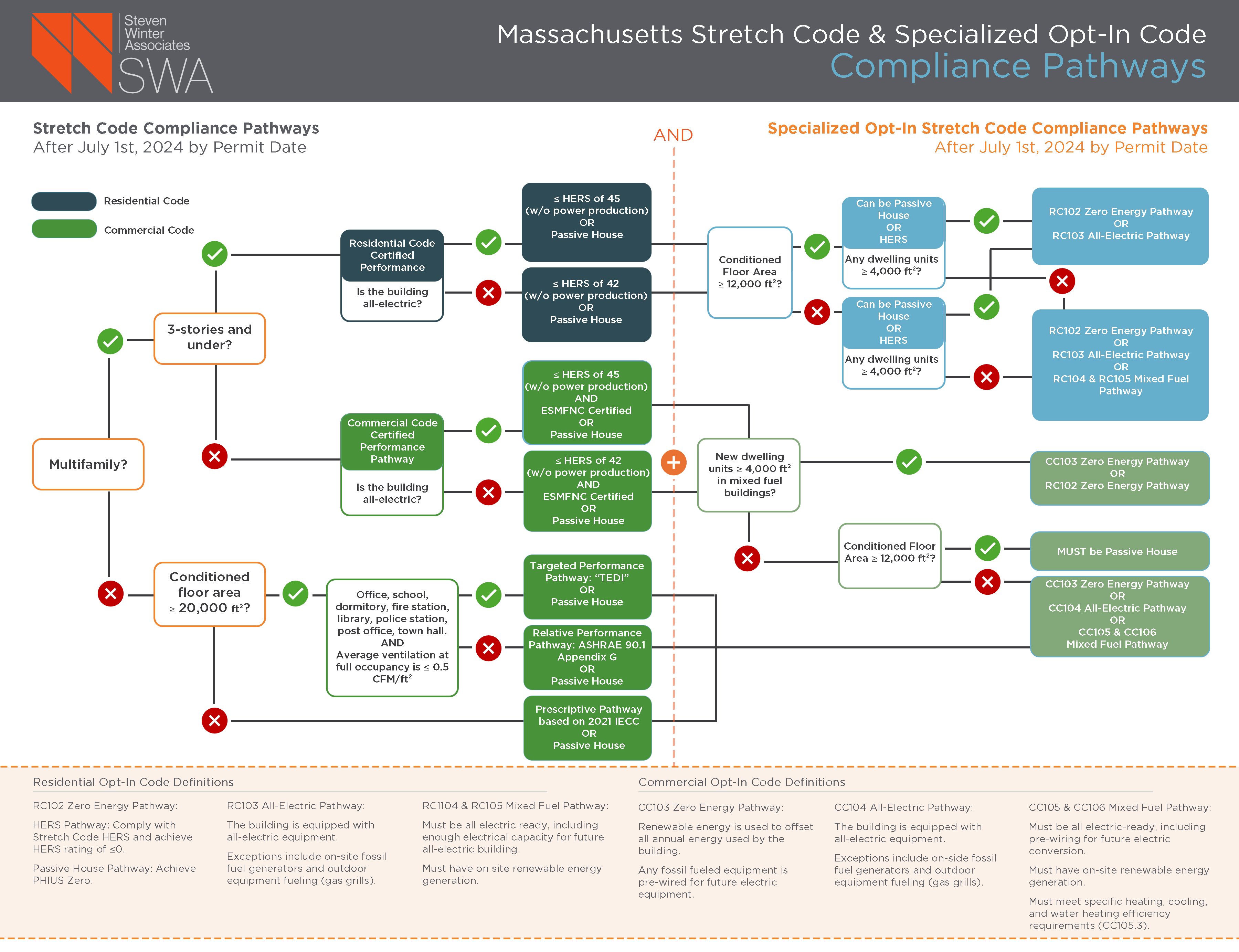

To evaluate code compliance pathways for commercial and multifamily buildings, refer to SWA’s decision tree (click here to download):

In municipalities using the stretch or specialized code, these three requirements will apply to all projects.

There is virtually no path through compliance without a balanced, energy recovery ventilation system.

For homes and dwelling units to previously meet ASHRAE 62.2 whole unit ventilation requirements, the following strategies were acceptable:

Exhaust- and supply-only can be part of a balanced ventilation system, and energy or heat recovery doesn’t guarantee a balanced system.

Energy recovery ventilation is required prescriptively, and it’s virtually impossible to make the targeted or performance paths work without balanced, energy recovery.

Project teams must specify an efficient energy recovery ventilator (ERV) or heat recovery ventilator (HRV) with a high total efficiency rating and low watts used per cfm delivered.

All buildings require third-party oversight and/or verification including, at a minimum, air infiltration testing and systems commissioning (Cx).

For commercial buildings with larger systems (typically central), Section C408 of the 2021 IECC requires that a plan, systems Cx, and a report are completed by a qualified Cx agent. Heating, cooling, and hot water systems in homes and multifamily dwelling units must also be verified and, in the case of ventilation and ductwork, tested for flow and leakage. These tested numbers, along with air infiltration, are included in the final HERS energy model and affect the final HERS Index.

Project teams must employ a third party. Depending on which code compliance path is being followed, this may include:

The stretch and specialized codes aggressively address carbon emissions reduction. To that end, eliminating the use of fossil fuels and combustion-producing equipment and appliances means the code prioritizes all-electric buildings.

Project teams using fossil fuels must install more robust energy efficiency measures (EEMs) such as insulation, windows, equipment, and appliances to compensate. If utilizing the HERS Index path, another way to offset EEMs is by reducing embodied carbon. (Get a more detailed explanation of embodied carbon in our blog post: How to Tackle Embodied Carbon Now: Low-Carbon Building Materials and Assessment Tools.)

To obtain a three-point HERS credit, project teams can meet R406.5.2 by reducing embodied carbon in either insulation or concrete as follows:

SWA raters work with project teams to identify which EEMs are feasible (i.e., available, constructable, cost effective) for their projects. During this analysis, we have discovered that typically, an all-electric building must install three of the following EEMs, in addition to an efficient ERV or HRV, to meet the HERS 45 target:

If receiving a three-point HERS credit for meeting embodied carbon reduction, a project might be able to eliminate one of the above EEMs and reduce upfront costs or installation and maintenance concerns.

For example, an electric-resistance water heater is a low-cost, low-maintenance appliance that doesn’t have the space or ducting restrictions of a heat pump water heater. But electric-resistance water heaters, due to their high energy use, typically bump up a HERS Index by at least three points. Since reducing embodied carbon in our building materials is a pressing issue, this may pencil out as a fair swap: reduce the carbon emissions in a major building component (i.e., insulation or concrete) in exchange for installing equipment that’s higher-emitting during the building’s operational stage.

SWA works with project teams at every phase of construction to ensure that buildings are on track to comply with all applicable codes. We can help with every step above; contact us to get started.

Contributor: Karla Butterfield, Sustainability Director

Steven Winter Associates